Schools flourish when they embed trust, distribute leadership of learning and live out democratic values. In this blog I explain why I think these are important and how schools can start putting them in place.

Swift trust

It’s quite amazing and life affirming, that in a crisis people suspend whatever is happening around them and rally to support a person(s) or to overcome a challenge. We often see the kinds of behaviours that amplify the best of us; creative problem-solving, selflessness, compassion and empathy. Time is a commodity which is usually limited but incredibly valuable. There is a need for learning and trust to form quickly between individuals, teams and organisations. Meyerson, Weick and Kramer (1996, pp 166-195) described this concept as ‘swift trust’.

Swift trust is constructed and sustained by heightened activity and responsiveness which is combined with a strong and positive expectation that the work of the group will benefit all involved (Coppola, Hiltz and Rotter, 2004, pp 95-104). Working to see of all students grow and achieve is, I would argue, the core purpose of schools. However, trust is rarely swift to form. Why is this? Surely the speed at which trust forms is not THE defining factor in forming a positive culture, it is the depth and extent. It is also complicated, but at the same time enriched by the sheer number and diversity of people involved.

Schools are exceedingly good at bringing groups of people together; students, staff and community. In the case of teachers, they are brought together for all manner of reasons – pastoral care of students, planning and moderating student learning and assessment, meetings and information sharing, research and for whole-school events. Another key time is collective learning and professional development. It is not unusual for training and work to be delivered by school leaders. This makes good sense because it could be said (although not always) that with experience comes expertise. School leaders generally have time and capacity to build and lead initiatives and are directly involved with whole-school strategy. The one question I have however, is what does their mere presence in, and/or leading learning, signify in terms of trust? Are school leaders perceived as instructional partners or simply ‘the bosses’?

What difference does leadership presence make? Testing the elasticity of trust.

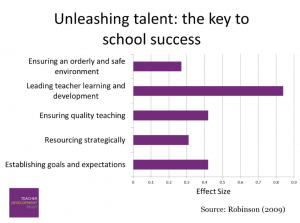

Robinson et al (2009) show us that there is strong correlation between some school leadership practices (especially the Principal) and student outcomes. In fact, ‘promoting and participating in teacher learning and development’ scored highest (0.84 ES) among the eight leadership practices identified. Can we infer from this that trust is evident in schools and therefore a difference maker, or is this about compliance? Either way, schools leaders need to initiate the trust cycle and work hard to see staff reciprocate that trust. They need to know what their impact is.

We have probably all been there (although some PD is like pedagogical waterboarding), caught in the moment, contributing and collaborating in learning, only to glance around and see a member of SLT. Perhaps a door quietly opens and a member of the leadership team slips in, hoping to go unnoticed. Does the atmosphere change? Do colleague’s behaviours default to a mode of compliance? Do they seem relaxed, fully engaged and share their thinking and work wilfully or under duress?

Leader’s self-awareness of their impact on PD is important. Contribution or critique can sometimes sting despite it being given with good intentions. For some, it can generate frustration, fear, and perhaps even a sense of failure. At worst it may trigger resentment, resistance and undermine self-efficacy. Communication can become stilted, people are unprepared to be vulnerable and involvement can feel like surveillance. I’m sure the last thing our school leaders want to do is reinforce hierarchy or authority and emphasise the division of labour. Instead they would prefer to see collective inquiry, reflection, shared values, risk-taking and innovation.

Megan Tschannen-Moran (2014) tells us that in adult learning (i.e. professional development), participant needs have to be understood and carefully considered in the design and delivery phases. In particular, she emphasises that ‘adults are relevancy oriented and must feel they have a reason for learning something, often connected to their role or social relationships’. In addition, they (generally) ‘prefer facilitation over instruction and practical application of learning over theory storage’. Above all, adult learners want to be trusted – trusted to undertake learning, apply learning, reflect on learning and contribute to learning. Enjoying the sensation of learning and being aware of what is making a difference is important. As Browning (2014) asserts, to be trusted, first you must give trust away. Do we hear leaders muttering ‘surely the wheels won’t come off if I am not involved?’

David Weston and the Teacher Development Trust have done great work in promoting powerful PD as a transformational element for schools in the UK. From their extensive research and collaboration with, for example, CUREE (Centre for the Use of Research and Evidence in Education) they have earmarked key approaches that make a difference. The diagram below beautifully illustrates some of the environmental factors that contribute to a healthy PD approach in schools. The section around culture is of particular significance. (D Weston, 2014 – ‘Powerful PD’)

Expand, refine and change

In my state of Queensland, teachers are required to complete 20 hours of professional development a year to maintain full registration. The guidelines regarding what constitutes PD are somewhat sketchy, but I applaud the fact that the profession is required to learn, upskill, share and contribute to a growing body of research, knowledge and practice. Some schools prescribe their quota of PD which align with whole-school development or improvement priorities. Others adopt a more organic approach, preferring to open the door to research, empowering their teachers to lead learning and development from the bottom up.

The profession is becoming far better at creating diverse professional development opportunities, loaded on the demand side. Technology has flattened connections and sharing learning generously has positively impacted many teachers and schools. ‘One-shot’, ‘spray-on’ (Mockler, 2005) or ‘drive-by’ (Senge et al 2000) professional development has been usurped by a myriad of grass-roots movements including Teach Meets, ResearchED, in-house, practitioner-led courses (which has the added benefit of schools not having to haemorrhage important budgets).

Going open has to an extent democratised PD and connected schools, resources and ideas across the globe. Does this mean the role of leadership in defining and governing learning and development is evaporating? I personally do not think so. Leaders simply needs to change its view. There will always be whole-school priorities, things which demand collective effort and responsibility. However, we do not have to all learn the same things, at the same times and in the same ways – much like our students. Furthermore, I would argue that leadership also need to exercise the vulnerability, risk-taking and learning they see their staff undertaking. This acknowledges that they are not above or beyond professional learning and strengthens trust as they assume the role of co-learner as opposed to a boss.

In conclusion, I believe Alma Harris (2013, pp83-5) is absolutely right to say that a principals and their leadership team’s primary role is to build relational trust. If this is grown, most other things follow including enhanced outcomes. She pulls it back to the four key aspects of trust and social capital building (Bryk and Schneider 2002) in the form of questions. I will leave you with them as they are really worth reflecting on regardless if you have a position of leadership or not.

- Respect – do we acknowledge one another’s dignity and ideas?

- Competence – do we believe in each other’s ability to fulfil our responsibilities?

- Personal regard – do we care about each other enough to go the extra mile?

- Integrity – do we trust each other to put children’s needs first even in the face of tough decisions?

Suggested Reading:

- Coppola, N W, Hiltz, S R and Rotter, N G, 2004, – Building Trust in Virtual Teams. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 47(2), pp 95–104

- Harris, A, 2013 – Distributed Leadership Matters: Perspectives, Practicalities and Potential. Corwin

- Meyerson, D, Weick, K E and Kramer, R M, 1996 – Swift Trust and Temporary Groups. In R M Kramer and T R Tyler (editors), Trust In Organizations: Frontiers Of Theory And Research, Thousand Oaks, California, USA, Sage Publications

- Tschannen-Moran, M and B, 2010 – Evocative Coaching. Jossey-Bass

great post – much needed common sense!

I really align with your thoughts on this Jon. Successful trust building in this domain requires authentic participation by leaders in developing approaches in partnership with staff.