Why innovate?

For nearly 20 years, I have been tinkering with my teaching practice. I’m a pedagogical fidget. From time-to-time I get asked ‘why don’t you just stick to what you know works?’ My reply, rightly or wrongly, is that I get bored easily. I know what some might say, ‘that’s irresponsible! Is your ‘fidgeting’ putting the students first?’ My rebuttal is straightforward – yes, I am. You see, I believe that it is in the best interests of my students that I have a repertoire of strategies to call upon, so I can design learning around their needs, rather than retrofit them into a plan.

My passion is building capacity and pedagogical dexterity with teachers. I am also a strong advocate for teachers as researchers and entrusting them to innovate their practice to improve outcomes. Furthermore, I love to see teachers enjoying their work and getting excited by new breakthroughs. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to contradict myself here by saying that research should solely lead to generating evidence, thus all practice should be evidence-based. Far from it. I have no problem with evidence-informed practice, if in fact it is in the best interests of students.

Innovation is a word regularly flung around by educators in all sorts of contexts – pedagogy, leadership, community engagement, I could go on. In any of these spaces, I don’t see innovation as homeopathy for education. It is also not entirely loose, unregulated and completely disruptive. In fact, innovation can be quite disciplined and intentional. Importantly, when innovating with practice, whether through an inquiry or research approach, teachers want to see whether something works or not. Yes, failure may occur and bring about learning, but ultimately the purpose is to make improvements of some form or to determine whether an approach, policy, strategy is no longer adding value and is obsolete.

The esteem part of innovation

There is something undeniably gratifying in seeing an innovation come off. As I have said in previous blogs, I believe professional and organisational trust is fundamental to building relationships and innovation. Teachers sense of worth and effectiveness is, I would argue, connected to how confident they feel that their work adds value. If we feel that we may put a foot wrong and student outcomes bottom-out or go pear-shaped, whose neck is on the block? Mine, is probably their perception. Who wields the axe? Who do I feel the heat from? Leadership? Parents? My colleagues? Myself? Surely, if I have tasted trust, support and outcomes have been solid, I have nothing to fear?

Innovating ones practice to modify planning, resourcing, thinking and outcomes can be exciting. It is strengthened if it is well researched, thoughtfully designed, supported by peers and leaders and stakes are lowered – i.e. little rides on it. Engaging with colleagues about innovations is also an interesting activity. Richard Elmore once asserted that ‘watching teams operate in schools is like watching astroturf growing’. I disagree with this. In well-functioning teams, innovation narratives can be transformative and affirming. Furthermore, if colleagues are committed to seeing improvement, research can liberate thinking and lead to ‘mining’ of ideas, new data and evidence to inform further iterations, all in the name of doing things differently and better for our students. It is understandable also though, that some colleagues can feel disappointed when innovation doesn’t work out, after all, so much is invested!

There is a dark side to innovation though. The profession has a Stockholm Syndrome with ‘measuring’ and an unhealthy fixation with data. I strongly recommend reading Carl Hendricks brilliant blog on this issue. When it comes to innovation, I personally prefer trust-based responsibility over accountability. This demands a shared understanding of the aims and objectives of innovation and negotiation can occur over counting what counts as progress. This in itself is a liberating thing as it is not tied to performance, but yields a raft of data and evidence that can be employed to inform future decisions, and that data and evidence has been produced by the owners of the process, teachers, who can also factor in and acknowledge control and bias. Schools-based innovation as Richard Olsen states here can lead to ‘qualitative growth in pedagogical quality, capacity and effectiveness’.

The Innovators Dilemma

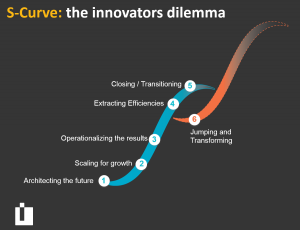

Valerie Hannon (Innovation Unit) alludes to what she calls the notion of the ‘innovators dilemma’ in her 2009 paper ‘Next Practice in Education – a Disciplined Approach to Innovation’. She explains that with any innovation, there is an inherent need for practice change (and subsequently outcomes – obviously). There has to be the acceptance that it could lead to the possible impacts of incremental or radical change. In normal improvement work, there is a fairly standard and linear 1,2,3,4,5 process (see below – Valerie Hannon/Innovation Unit). However, innovation seeks to capitalise on the previous best and set a new trajectory (6). This space in between is messy, tense and unsettling and requires careful support and handing by leadership. It is also exciting.

It is my experience that this is where innovation gets a bad name. New practices, new data and metrics and new ways of working involve change. The change element often magnetises the headlines over the learning or successes of innovating. I find this sad, because fundamentally, what we are doing models what we ask students to do, learn, practice and apply. Stories of learning are powerful, especially amongst teachers. The learning is THEIRS. The experience is THEIRS, the process has been THEIRS.

So next time you are working through a review of practice and considering innovating, what will you let grab the headlines or publicise? Handling change requires sensitivity as too much, too soon (which is poorly planned) can cause fatigue. Lasting and value-adding change occurs if the positive outcomes of innovation are implemented off the back of teachers owning the learning and development. It should lead to scaling and if the diffusion strategies are determined by teachers, it should be enjoyable!